Your Health is in your gut

Growing evidence indicates that the gut is pivotal in human health and the progression of many diseases, including inflammatory conditions, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, mental health issues, and cancer. It is the principal organ tasked with digesting the food we consume and absorbing nutrients. The gut underpins all bodily functions, from energy production and hormonal balance to mental well-being, skin condition, and the elimination of toxins and waste. It is estimated that roughly 70% of the immune system resides within the gut.

The most important factor associated with your gut health is your gut microbiome.

What is the gut microbiome?

Our bodies harbour roughly 10^14 microbial cells, with the majority residing in our gut. These microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and other species (ranging from 100 to 1000 different types), have co-evolved with humans since our inception.

They play a crucial role in numerous health aspects. Adverse alterations in the gut microbiome have been linked to a variety of diseases and conditions.

Dysbiosis, or the imbalance of gut microbiome, is mainly marked by a reduced diversity and quantity of bacteria and fungi, particularly those linked to dysfunction and various diseases.

Unfortunately, a Western diet, prolonged stress, lack of sleep, alcohol consumption, and smoking all contribute to the development of an unhealthy gut microbiome

The gut microbiome is crucial for host metabolism and is significantly shaped by an individual's long-term diet, yet it can also adapt rapidly to substantial changes. Therefore, the gut microbiome provides a vital insight into the impacts of diet and lifestyle choices.

Microorganisms in the distal gut enhance host health by synthesizing vitamins and essential amino acids, and by producing significant metabolic by-products from dietary elements that remain undigested by the small intestine.

Recent advances in genome sequencing technologies, bioinformatics, and culturomics have empowered researchers to investigate the microbiota, their roles, and their influence on our health and the development of diseases.

Our diet and geographical environment are two primary determinants of the structure and function of our microbiome

Rural indigenous populations are known to possess a significant diversity in their gut microbiome, hosting microorganisms absent in industrialized populations. The depletion of these indigenous microbes might be a key factor in explaining the surge of chronic diseases in modern society.

The choices you make in your daily diet significantly affect your gut microbiome

The microorganisms in your gut thrive on dietary fiber, so consuming a variety of vegetables, fruits, beans, seeds, nuts, and whole grains, which are all rich in fiber, can enhance the diversity of your microbiome.

A healthy gut features a varied microbial community, and a diverse diet promotes the proliferation of beneficial bacteria. Specific types of fibre and carbohydrates are particularly effective at fostering the growth of these friendly gut bacteria.

These ingredients, known as prebiotic foods, are a simple addition to your diet. Foods such as onions, spring onions, garlic, cabbage, oats, flaxseeds, apples, asparagus, nectarines, blueberries, and bananas all have prebiotic properties.

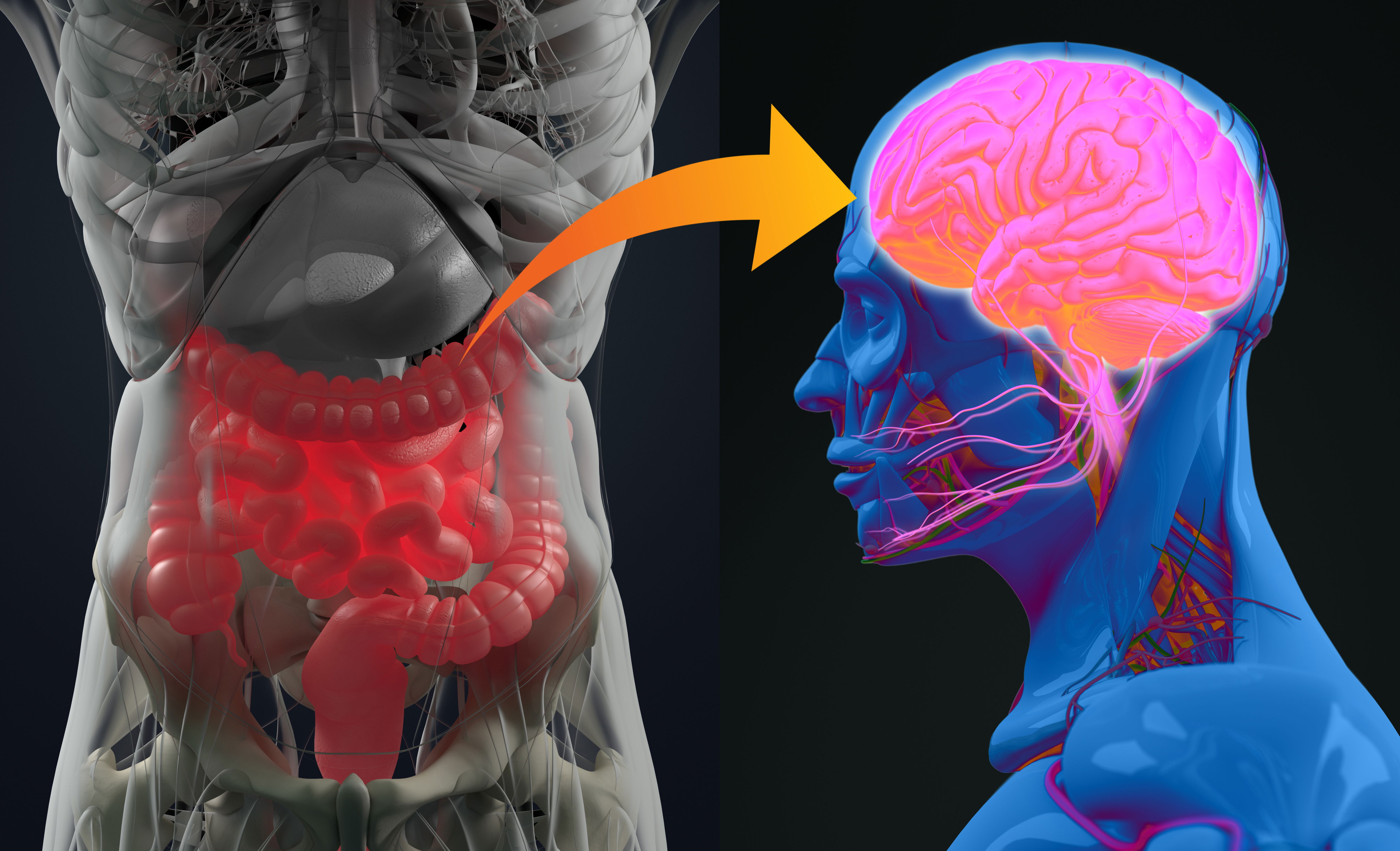

Increasing evidence supports the connection between the gut microbiome and mental health

Research indicates that gut microbiome can affect brain function via neural, hormonal, and immune pathways.

For instance, gut microbiota might compromise the intestinal barrier's integrity, leading to the release of cytokines that communicate with the brain or traverse the blood-brain barrier. Additionally, metabolites produced by gut microbiome could enter the brain via the bloodstream if not absorbed.

Two randomized controlled trials explored the impact of a four-week probiotic regimen on brain activity in healthy individuals. Those who received live bacteria reported increased vitality and less mental fatigue compared to the placebo group.

In a separate trial involving multispecies probiotics, subjects reported a higher positive affect and exhibited distinct BOLD signal patterns (blood-oxygen level-dependent) during emotional decision-making and memory tasks, unlike the placebo group.

Further research assessing the influence of probiotics on depressive symptoms has shown that enhancing gut flora significantly reduces depression symptoms in individuals with mild to moderate depression.

Specifically, Miyaoka et al., (2017) study on 40 patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) on antidepressants found that adding probiotics to the treatment improved depression outcomes more than antidepressants alone, with high treatment response and remission rates of 70% and 35%, respectively.

The study involving health college students who received multispecies probiotics reported improvements in panic anxiety, neurophysiological anxiety, negative affect, and worry, as well as enhanced regulation of negative mood in the probiotic group compared to the placebo group.

The bacteria residing in our gut are highly susceptible to stress and its mediators

Gut bacteria react to stress-related neurochemicals released by the host, potentially influencing the outcome of bacterial infections. Current theories propose that bacteria serve as carriers for neuroactive compounds, impacting host physiology.

There is compelling evidence linking the gut microbiome's composition to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, autoimmune arthritis, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and atherosclerosis.

Additionally, microbiota transplants from obese to lean mice indicate that the obese condition can be transferred, possibly due to microbiota with a greater ability to extract energy from the host's diet.

Recent research also indicates that gut bacteria produce substantial amounts of amyloids and lipopolysaccharides, which play a significant role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Your immune system is largely housed in your gut

The intestinal mucosal immune system is the largest immune component in humans and works in close conjunction with the intestinal microbiome. Maintaining the balance of the intestinal mucosal immune system is crucial for host homeostasis and defence.

The intestinal microbiota and mucosal immunity are in constant interaction to maintain this balance. Disruption of this balance can lead to the dysfunction of the intestinal immune system, which may cause various diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBD).

IBD is a complex disease affected by genetic, environmental, and microbial factors that can lead to intestinal inflammation through an abnormal immune response. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are common forms of IBD.

The gut microbiome influences both skin health and the cellular aging process

Understanding the link between the gut microbiome and healthy aging is crucial for longevity and an extended health span. Cellular senescence, or biological aging, is a promising research area linked to microbial dysbiosis.

Recent data indicate a complex relationship between the gut microbiome, cellular senescence, and skin health. Additionally, bacterial metabolites present in the skin, resulting from gut-skin interaction, can substantially affect skin health.

Gut microbiome has an impact on cancer development and treatment

Regrettably, there has been an increase in cancer diagnoses especially among young people in recent years. Tumorigenesis, associated with the gut microbiome, is one of the most extensively researched pathologies. This link is evident in both local gastrointestinal cancers and distal tumours.

Recent research indicates that dysbiosis of the gut microbiome may be connected to various cancers. The gut microbiome can influence the progression of distant tumours, the side effects of treatments, and the immune system's response to cancer cells.

On the other hand, certain microbiota subpopulations may proliferate during pathological dysbiosis, producing high toxin levels that can initiate inflammation and tumorigenesis. The gut microbiome and its metabolites may serve as either cancer promoters or inhibitors.

Beneficial effects have been associated with specific bacteria, which could lead to personalized treatments. Analysing and targeting a patient's microbial composition and function is crucial for the future of multidisciplinary and precision medicine.

The gut microbiome is associated with the development of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 Diabetes

Despite the availability of various treatments, the incidence of diabetes and its complications continues to increase. A new promising approach targets the modulation of gut microbiota using probiotics, prebiotics, symbiotics, and faecal microbial transplantation.

The significant differences in gut microbiota composition have been observed in preclinical animal models and patients with type 2 Diabetes compared to healthy controls. The severity of gut microbiota dysbiosis correlated with the severity of the disease, and the use of probiotics for restoration in both animal models and human patients has shown improvements in symptoms and a slowdown in disease progression.

These observations and studies highlight the crucial role of microorganisms in human health and indicate that altering them could impact disease progression. The dynamics of gut microbiota are indeed affected by one's lifestyle and diet. The decision is yours if you wish to alter your lifestyle and embark on a journey towards health and longevity.

Read more 8 SIMPLE STEPS TO IMPROVE GUT MICROBIOME

WHY THE GUT HEALTH SHOULD BE YOUR No.1 NEW YEAR'S RESOLUTION

References:

Adak A, Khan MR – An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 76:473-493, 2019.

Bidell MR, Hobbs ALV, Lodise TP - Gut microbiome health and dysbiosis: A clinical primer. Review of Therapeutics 42:849-857, 2022.

Boyajian JL, Ghebretatios M , Schaly S, Islam P, Prakash S - Microbiome and Human Aging: Probiotic and Prebiotic Potentials in Longevity, Skin Health and Cellular Senescence. Nutrients 13, 4550, 2021.

Brown EM, Clardy J, Xavier RJ - Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host Microbe 31(2): 173-186, 2023.

Cresci GA, Bawden E - The Gut Microbiome: What we do and don’t know. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 30(6): 734–746, 2015.

Iatcu CO, Steen A, Covasa M - Gut Microbiota and Complications of Type-2 Diabetes. Nutrients 14:166, 2022. Jarbrink-Sehgal E, Andreasson A – The gut microbiota and mental health in adults. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 62: 102-114, 2020.

Manor O, Lovejoy JC, Gibbons SM, Dai CL, Kornilov SA, Smith B, Price ND, Magis AT - Health and disease markers correlate with gut microbiome composition across thousands of people. Nature Communications 11:5206, 2020.

Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E, Turroni F, Mahony, J, Belzer C, Delgado Palacio S, Arboleya Montes S, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Rodriguez JM , Bode L,de Vos W, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, Sinderen D, Venturaa M – The First Microbial Colonizers of the Human Gut: Composition, Activities, and Health Implications of the Infant Gut. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 81(4), 2017.

Miyaoka T, Kanayama M, Wake M, Hashioka R, Hayashida S, Nagahama M et al - Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 as adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. A prospective open-label trial. Clinical Neuropharmacology 41(5): 151-155, 2018.

Shi N, Li N, Duan X, Niu H - Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Military Medical Research 4:14, 2017.

Singh RK, Chang HW, Yang D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, Bhutani T, Liao W - Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine 15:73, 2017.

Tong Y, Gao H, Qi Q, Liu X, Li Y, Gao J, Li P, Wang Y, Du L, Wang C - High fat diet, gut microbiome and gastrointestinal cancer. Theranostics 11(12)5889-5910, 2021.

Vangay P,1 Johnson AJ,Ward TL, Al-Ghalith GA, Shields-Cutler RR, Hillmann BM,Lucas LK, Beura LK, Thompson EA, Till LM, Batres R, Paw B, Pergament SL, Saenyakul P, Xiong M, Kim AD, Kim G, Masopust D, Martens EC, Angkurawaranon C, McGready R, Kashyap PC, Culhane-Pera KA, Knights D - U.S. immigration westernizes the human gut microbiome. Cell 175(4): 962-972, 2018.

Example Text